1. Introduction

Today,

I will discuss one of the security basics named “Physical Security

Concepts”. It covers issues related to Physical Security as a key

component of a comprehensive organizational approach to security.

2. Key Learning Objective

After completing this session, you should be able to:

2.1. Describe the goals of physical security controls

2.2. Explain the design features of countermeasures

2.3. List the goals of a physical security plan

2.4. List the three (3) levels of barrier protection

2.5. Describe the three (3) types of barriers

2.6. Discuss the features of a disaster recovery plan

2.7. List the factors used in a perception plan

2.8. List and discuss the three (3) elements used in protection lighting

2.9. Identify the protection objectives of illusory techniques

2.10. Describe the components of incident response

2.11. Explain the three (3) functional objectives of protective lighting

2.12. Discuss the strategies of object illumination design

3. Physical Security Controls

Providing

an organization or site with effective security involves several

factors, some relatively obvious, others less so. The intent of Physical

Security is to control access and prevent the interruption of

operations. These goals are accomplished using tangible countermeasures

ranging from fencing and lighting to electronic surveillance equipment

and carefully defined policies and procedures.

Keep

in mind that the actual Physical Security "controls" — the materials,

equipment, and procedures used in securing a site — are only one element

of an in-depth program of protection. Indeed, an effective component of

many security systems is the perception of security both on the part of

authorized personnel on site and potential intruders. Similarly, the

use of barriers and lighting systems provide two important deterrents to

potential intrusion:

3.1. Physical deterrence

3.2. Psychological deterrence, as a consequence of perceived impediments to successful intrusion

4. Design Considerations for Physical Security

As mentioned above, Physical Security provides a "suite" of countermeasures designed to:

Ensure effective access control;

Minimize the possibility of interruption of operations.

In order to accomplish these goals, every Physical Security plan includes the following countermeasures:

4.1. Policies and procedures - comprehensive security goals and plans and how they will be implemented

4.2. Personnel - System administrators, operators, guards, etc.

4.3. Barriers- which are access control systems or structures

4.4. Equipment- including hardware and software, such as detection devices, alarm devices, communication systems

4.5. Records- of historical and incident reports, access records and other logs

5. Barriers as a Means of Access Control

The

goal of in-depth protection is achieved by controlling access through

the use of barriers. Barriers are any means used to control the flow of

access to an area.

Barriers

are typically arranged in concentric layers. The region which is the

object of the protection is at the center, with the lowest level of

security obviously residing at the outermost layer. Each layer closer to

the center has a progressively higher level of security. The objective

is to deter or delay an intruder as much as possible. In most security

plans, three layers of barrier protection can be identified: outer,

middle and inner.

Barriers

define the physical limits of an area and prevent the penetration of

that area by an intruder (either human or animal). Barriers are used to

discourage penetration by accident, by force or by surreptitious means.

Barriers should be designed to prevent an accidental penetration,

constructed to defeat the expected force used in a penetration or to

detect a penetration by stealth. Barrier should always be constructed

with the understanding that additional countermeasures may be needed to

improve the barrier's capability.

Barriers

physically or psychologically deter or discourage the undetermined

intruder, delay the determined intruder, and channel the flow of traffic

through entrances. Barriers may be either natural or artificial (or

structural). Natural barriers include bodies of water, mountains,

marshes, deserts or other terrain difficult to traverse. Structural

barriers are man-made entities such as fences or walls.

6. Exterior Barriers – Design Considerations

Exterior

barriers (fences, walls, etc.) must include two "clear zones" – one on

either side of the barrier. Each zone should be 20 feet or more of open

space. The purpose of a clear zone is to provide an unobstructed view of

the barrier and surrounding area. When a barrier surrounds a structure,

a clear zone of at least 50 feet should be between the perimeter

barrier and the structure. The exception to this rule is when a building

wall forms part of the perimeter barrier.

7. Building Surfaces as Barriers

Building

surfaces (walls, floors, ceilings, and roofs) are not typically

designed to be barriers; however, such surfaces do deter penetration.

For example, an exterior surface usually consists of at least two layers

of material. While an exterior wall is primarily designed to address

structural and environmental issues — building stability and comfort —

such surfaces also serve to prevent intrusion.

Each

building surface must be evaluated for its effectiveness as a

structural barrier when used as part of the primary barrier. When evaluating building surfaces for security barriers, system designers must perform either a physical inspection of the surface or a review of the architectural and engineering drawings. It is recommended that both techniques be utilized whenever possible.

Perhaps

the most significant weakness in building surfaces as security barriers

are openings such as doors, windows, and overhead doors. Often their

design pays only minimal attention to security issues. For example,

typically, the frame or doorway serves only to hold a window or door in

place. A frame or door jamb is not structural in that it is simply set

into an opening in the building surface. As a result a doorway may be

easily split and broken apart. In addition, the door itself it often

weaker than the frame and may be easily compromised.

Another

weak point may be the hinges. Inexpensive hinges or hinges installed

without attention to security may be easily defeated, although when

hinges are tampered with, evidence often remains.

So today is it. In my next articles I will discuss Layer of barrier, type of barrier, protection perception

(Part- 2)

1. Introduction

Today,

I will discuss one of the security basics named “Physical Security

Concepts”. It covers issues related to Physical Security as a key

component of a comprehensive organizational approach to security. In my

last article (Part-1) I have discussed Design consideration of physical security and barrier.

2. The Three Layers of Barrier Protection

The

outer protective layer may consist of fencing, natural barriers,

lighting systems, signs, and alarm systems. These controls generally

accomplish two related functions:

- Defining property lines

- Channeling personnel and vehicles through designated access points.

The

middle layer of barrier protection is usually considered to begin at

the exteriors of any buildings on the site. Features may include:

- Lighting systems

- Alarm systems

- Locking devices

- Bars or grill work

- Signs

- Additional fencing.

More

positive controls are used at this level than at the outer layer.

Ideally, those planning security for a site must consider each building

to be a six-sided box. Barrier design, therefore, should include

provisions for protection from roof entry as well as intrusion from

underground.

The

inner lay may itself consist of several levels. This inner and final

barrier against intrusion will ensure that an intruder (any person

attempting to enter a region who at any given moment may not be

authorized to do so) will be detected even if the outer and middle

layers of protection have failed to do so. Items or areas that could be

protected are research/production data, equipment necessary to conduct

operations, sensitive/competitive processes, negotiable instruments,

critical organizational records, computer rooms, etc.

The

security design of the inner barrier layer also prevents the intruder

from accessing anything deemed to have value. Features may include:

- Window/door bars

- Locking devices

- Barriers, signs

- Access/intrusion/alarm systems

- Communication systems

- Lighting systems

- Safes and controlled areas

3. Types of Barriers: Natural, Structural, Human

Effective barriers need not be necessarily man-made. Barriers against intrusion may be naturally occurring, man-made, or human.

Natural barriers should be considered as part of a security plan. Natural barriers include:

- Bodies of water, including rivers, creeks and lakes

- Woods

- Cliffs

- Wild hedge plant

In addition to being effective outer layer barriers, natural barriers can be quite cost effective.

Structural

barriers are man-made (or natural barriers manipulated by security

designers). They are placed at strategic locations around a site to

control access. Structural barriers include:

- Berms - man-made hillocks

- Retention ponds

- Planted tree lines to define boundaries

- Walls

- Fences

- Doors, gates, and locking mechanisms

- Ditches

- Posts

- Bollards - stanchions controlling traffic flow

- Glazing materials.

The

third type of barrier comes in the form of a human presence. Here the

security design uses people to control access and limit movement areas.

Human barriers may be in use in any of the three layers of barrier

protection. Personnel used to provide human barriers include:

- Public safety/police

- Contract/proprietary security officers

- Receptionists.

4. Preventing Interruption of Operations

For

many organizations, it is not enough to keep unauthorized personnel out

of secure areas. More is required. If operations are interrupted, the

results can have a serious negative impact on the organization, its

employees, the people it serves, and the community of which it is a

part. Because of the importance of maintaining normal operations,

minimizing the potential interruption of operations is the second major

goal of an in-depth physical security plan. When thinking about

interruptions to operations, sabotage and vandalism are certainly

important security considerations; however, such interruptions can also

be caused by natural disasters, environmental disasters, or industrial

accidents.

A

well-designed Physical Security plan must incorporate policies and

procedures to ensure continued operations even should one of the above

situations occur. A comprehensive approach to Physical Security must

include disaster recovery plans. Such plans must include:

- Evacuation procedures

- Marshaling of resources to deal with the emergency event

- Maintaining order on the site

- Administering first aid and directing emergency services and operations

- The protection of assets (personnel and property).

The

presence on-site of hazardous materials adds to the challenges and

complexity of a disaster recovery plan. An event involving such

materials may require highly specialized response utilizing equipment

and personnel far beyond the scope of non-Haz Mat events. Plans designed

in response to potential hazardous material incidents must be developed

with local and possibly even national public safety assistance, being

sure to meet country environmental safety regulations. The plan must

address issues such as:

- Relocation of materials

- Containing spills

- Minimizing losses and contamination of personnel and property

- Notification to proper authorities and employees

- Securing affected areas to prevent unauthorized entry.

5. Perception as Protection

Clearly

a major goal of any physical security plan is to ensure employees,

customers, visitors and vendors are secure. In reality, accomplishing

this goal requires security planners to look beyond the arrangement of

barriers, the institution of access control, etc. Security personnel may

know all prudent and expedient measures have been taken to ensure a

high level of security. If, however, workers, customers, and others do

not feel secure, then even the best efforts of the security department

will have failed.

For

a security plan to be truly effective, employees, customers, visitors

and vendors must perceive they are secure; they must believe they are in

a safe and secure environment. Consider the effect of a simple

homeowner security device — a sign that read, "Beware of the Dog." You

do not need to see the dog for it to have an effect. Designers of an

effective security plan must recognize the key role "perception" plays

in providing protection — and not just from the point of view of

authorized personnel at a site, but from the viewpoint of potential

intruders as well.

First,

to incorporate elements in a security plan which will ensure a

"perception of security," planners should begin by identifying factors

and security issues that concern persons at work and visiting the site.

What fears do these persons have and what are reasons for these fears?

Next,

a physical security plan must involve all groups within an

organization. From the start, security must be viewed by all as part of

every employee's responsibility. All personnel must understand that they

play an important role in the organization's security program.

Every

element of the Physical Security Plan should be reviewed not only for

its ability to reduce unauthorized entry and loss prevention but also

its ability to create the perception of a safe and secure environment.

To restate this, effective security protection consists not only of the

actual measure taken, but also the perception of protection it presents.

For example, a studies have shown fencing topped with barbed wire can

be breached by knowledgeable intruders in under ten seconds. For many

people, however, this same fence may appear impossible or difficult to

breach, and therefore will provide an initial deterrence.

In

many organizations, including retail store operations, security

programs can be enhanced by the use of devices, such as signs and dummy

CCTV cameras (e.g., the mirrored half-dome CCTV enclosure) to create or

heighten the illusion of protection. An individual only has to see the

dome — not any camera which may be inside it — to understand he or she

may be under surveillance.

In summary, effective protection schemes must incorporate three approaches to security:

- Visible with real protection

- Not visible with real protection

- Presenting the appearance of protection but in fact an illusion.

I have to finish here. In the following articles, I will provide more detail in designing such a protection plan.

(Part-3)

1. Introduction

In my last two discussions (Part-1) and (Part-2),

I have discussed Design consideration of physical security, Barriers,

Layers of barriers, Type of Barriers and perception of protection.

Today, I will discuss the Protection Scheme Guidelines as below:

1.1 Protection Scheme Guidelines

1.2 Guidelines for Illusory Techniques

1.3 An Essential Ingredient: Incident Response

1.4 Cost Impact on Security Plans

1.5 Guidelines for Protective Lighting

1.6 Object/Area Illumination

1.7 Lighting as a Physical Deterrent

1.8 Lighting as a Psychological Deterrent

1.9 Security Lighting Standards

2. Protection Scheme Guidelines

Developing

an effective Physical Security plan involves a series of logical steps.

While the specific content developed during these steps varies from

organization to organization, the basic steps remain the same. The first

step is to perform a "Vulnerability Assessment." (This process was

discussed in "Security Principles and Operation-Part 3".)

Based on this assessment, as developed for a particular organization,

security planners can identify specific "protection objectives" for the

organization. At this point, planners can determine what techniques and

equipment will be required to accomplish the objectives. Included in

this step is a determination of which objectives may be supported with

illusory techniques.

3. Guidelines for Illusory Techniques

Establishing

the image of security requires an assessment of what types of illusions

might be utilized and how they will relate to the tangible security

assets of the program.

One

word of caution, regarding illusory techniques: occasional failures of

illusory techniques occur — as in shoplifting in a department store's

ready-to-wear department. It may be that some loss is acceptable in such

a store's security plan for that department. Now consider the same

department store, but this time the jewelry department. Here any loss is

deemed unacceptable. Armed with these two pieces of information, the

security designers for the store can plan an appropriate security

response to the potential threats. In the case of the ready-to-wear

department, it may be that the use of simulated CCTV domes is

appropriate. On the other hand, when it comes to the jewelry department,

the same planners may call for a series of domes actually containing

functioning CCTV surveillance cameras. At each location, appropriate

signage warning of surveillance may further deter potential threats.

Clearly in this setting, a variety of security options is appropriate.

Therefore, real techniques (CCTV, alarm systems, and signage) in

combination with illusory techniques (simulated CCTV domes) is deemed to

provide effective levels of protection.

When

these techniques are combined with procedures such as selected

prosecution of violators, the organization — in this case the store —

can create a comprehensive and effective security plan.

A

note of caution: once an illusory technique has been compromised, it

has no further value and should be immediately discontinued. In order to

prevent this from occurring, it is essential to keep the actual number

of personnel who know the true aspects of the security plan to the

absolute minimum.

4. An Essential Ingredient: Incident Response

A

key component to ensuring the on-going effectiveness of a security plan

is the consistent and predictable response to any incidents that may

occur. The security plan, therefore, should have clearly defined

responses in place in the event of an incident. Such responses should be

balanced in their effect. They must be designed to be both preventative

(discouraging attempted threats) and punitive (punishing the current

offender).

A

preventative response is initiated before the unauthorized person

reaches the protected objective. It is designed primarily to be a clear

warning that additional response capabilities are in place. As such a

preventative response is intended to discourage continued attempts and

to turn away the intruder.

A

punitive response is initiated once the penetration has occurred or is

still in progress. Rather than turning away an intruder, the objective

of punitive responses is the identification and apprehension of the

perpetrator. An example of a punitive response is the capture of a

robber resulting from a police response to a silent alarm from a bank.

Balanced

response it the preferred methodology and involves both of the previous

responses used singularly or in combination throughout the security

plan.

5. Cost Impact on Security Plans

A

final consideration in a protection scheme is financial: available

funds versus costs. Obviously sufficient funding must be available to

provide adequate protection based upon the risk management profile.

Funds must be sufficient to cover costs associated with personnel,

training, equipment, and maintenance requirements. The cost of the

system must be viewed in contrast to the potential cost of losses

resulting from inadequate security measures. This kind of analysis can

be an important aid as decisions are made regarding funding levels for

an organization's security plan.

6. Guidelines for Protective Lighting

An

important component of a comprehensive security plan is lighting.

Security Protective Lighting has three functional objectives:

6.1 To illuminate a person, object, place or condition of security to permit observation and identification

6.2 To be a physical deterrent through the glare effect of direct light on the human eye

6.3

To be a psychological deterrent creating in an intruder's mind the

awareness that he or she will be discovered and observed during any

unauthorized entry attempt.

7. Object/Area Illumination

The

most obvious reason for protective lighting is to make certain any

person, object, place or condition will be sufficiently illuminated to

provide effective security in a given region. In order to assure

sufficient illumination a number of conditions must be met. For example,

lighting designers must consider natural properties of reflectance,

light absorption capacity, mobility and an object's inherent sensitivity

to light. All these factors affect an entity's visibility. Other

factors to consider include:

7.1

The schedule of observation. Will the observation be constant or

intermittent? If intermittent what will the frequency of observation be

and will the observation be performed on a regular or random basis

7.2

The means of observation. Will the observation be performed by a person

or CCTV system? In either case, sufficient illumination must be

available to accomplish the observation. For CCTV, the camera

specifications will list required illumination.

7.3

The area and quality of coverage. Is it necessary to observe all

details in the area of coverage, or will only selected elements within

the area be of interest? What level of detail is necessary? Is it

necessary, for example, to observe changes in color? This clearly would

affect decisions regarding the "quality" of the illumination, in this

case color temperature, specifically.

7.4

Reliability of the illumination devices. If, for example, observation

is to be constant, equipment mean time between failure rates as well as

back-up power source must be considered. In addition, system designers

must factor in restoration time of illuminating devices when a power

failure occurs. Some lamps require several minutes of operation before

they reach their specified levels of illumination output and quality.

When

considering an illumination system for protection, the answers to these

questions are essential in implementing a system which meets the

organization's requirements.

8. Lighting as a Physical Deterrent

In

addition to providing simple illumination in an area of coverage,

protective lighting may be given a more "active" role in deterring

intrusion. One factor in the effectiveness of lighting used in this

manner is it's brightness and position in relation to the intruder.

Earlier I referred to this as the "glare effect." Consider the

disorienting effect (and therefore deterring effect) of suddenly filling

an area with high levels of illumination triggered by an intrusion

detection device. If this is a component of a lighting system design,

note that such an effect may be enhanced by keeping an area in low light

levels until an intruder is detected.

When protective lighting will be used as a physical deterrence, the following questions must be considered:

8.1

Will the system be continuously deployed or event activated? It may be

deemed useful to provide continuous illumination. (This may provide a

psychological effect as well as actual.) On the other hand, depending on

the area of coverage and design objectives, the lighting system may be

event activated; that is, a specific event (detected intrusion, time

period, etc.) may trigger the lighting system to be turned on.

8.2

Will the system be target oriented or omni-directional? In some

situation, it may be desirable to illuminate an entire area of coverage.

In other settings and with different security requirements, target

oriented illumination may be sufficient, providing, in effect, pools of

light illuminating only specific objects or locations within the same

area of interest.

8.3 Will the protective lighting system be interface with CCTV or alarm systems?

What failure rates of system components or simultaneous element failures are the most critical to overall system performance?

8.4

Could the system be accidentally activated this causing an injury or

damage? This is an issue that must receive special consideration it if

is to be event activated.

9. Lighting as a Psychological Deterrent

Designers

of a protective lighting system may, in any given region (area of

coverage) and circumstance, use lighting primarily as a psychological

deterrent. Recalls that lighting as a psychological deterrent creates in

an intruder’s mind the awareness that he or she will be discovered and

observed during any unauthorized entry attempt. As a general rule,

however, designers may view psychological deterrence more as an added

benefit, given specific situations (in a design intended primarily for

object illumination or physical deterrence). When lighting is used as a

psychological deterrent, it is imperative that the lighting system be

interfaced with CCTV, alarm systems and security response forces. This

is essential in order to ensure maximum deterrent effect.

10. Security Lighting Standards

Many

turn to The U.S. Army Field Manual 19-30, Physical Security. This

manual has been used as a reference for protective or security lighting

for many years. Another resource, the Illuminating Engineers Society

(IES), Lighting Handbook, 1993, also serves as a reference for

protective and security lighting. The third source of information on

this subject is the Nuclear Regulatory Commission Physical Security

Standards. This document provides in-depth discussions on isolation

zones, protected areas, clear zones and other restricted areas requiring

protective lighting. These three resources provide essential

information. Latter on, I will discuss details of any one Security

Lighting Standards.

In my next articles, I will discuss elaborately Lighting Applications Issues.

(Part-4)

1. Introduction

In my last three discussions (Part-1), (Part-2) and (Part-3),

I have discussed Design consideration of Physical Security, Barriers,

Layers of Barriers, Type of Barriers, Perception of Protection and use

of lighting as physical and psychological deterrent. Today, I will

discuss how to design Security Lighting at workplace.

The following issues will be discussed in this article:

Application Issues

Light Intensity for Object/Area Illumination - Design Issues

Light Intensity for Physical Deterrence - Design Issues

Light Intensity for Psychological Deterrence - Design Issues

Types of Lamps

Illumination Quality

2. Application Issues

It

should be apparent from the discussions in the preceding articles that

lighting requirements vary according to each security application

(object illumination, physical deterrence, psychological deterrence).

All of these applications have different requirements for intensity,

distribution, quality, sources and reliability. In addition, appropriate

lighting for a given area is affected not just for the requirements of

the security plan for the area, but by conditions in the surrounding

areas as well.

For

example, a designer's plan for protective lighting must account for the

impact lighting from an adjacent property, especially if there is

resulting glare. In the following sections, we will focus on

illumination intensity and quality in more detail.

3. Light Intensity for Object/Area Illumination - Design Issues

With

object illumination, the goal is to provide sufficient light over the

area to detect anyone moving in or around the area. At the same time,

lighting systems should whenever possible limit the intruder's view of

the area. This strategy is intended to impair the intruder's ability to

ascertain whether they are under observation.

An effective security lighting system for object illumination should:

3.1 Discourage intruders

3.2 Make detection of attempted entry highly probable

3.3 Avoid glare that annoys neighbors, workers, security officers or passing traffic

3.4 Provide adequate illumination whether the surveillance is by electronics or the human eye

3.5 Render the observance of security posts, CCTV cameras or other electronic sensors by intruders to an imperceptible level

3.6 Provide for special treatment of entrances, exits and other sensitive locations.

Further,

such a lighting system must be designed with careful attention to

several additional factors that impact on its overall efficiency. System

designers should:

3.7 Provide reliability through redundancy of components

3.8 Provide for easy control and maintenance

3.9 Determine the required illumination by viewing the scene under varying natural light conditions

3.10

Determine the distance between the surveillance element (person,

camera) and each element of the illuminated object or scene

3.11. Determine the purpose of the observation: recognition, identification or detection.

Each

of these factors is a crucial design element which, when applied

properly to the overall lighting plan, will yield a highly effective and

efficient protection capability.

4. Light Intensity for Physical Deterrence - Design Issues

Lighting

intended to provide physical deterrence must use lighting intensity as a

method to disable an intruder. The general design principle for

physical deterrence lighting is use a level of intensity as low as

possible to accomplish the desired effect. An effective lighting system

for physical deterrence should:

4.1 Cause an inability to see normally, preventing further penetration of the area

4.2 Cause specific physiological reactions to the light such as pain or tearing and change in ocular muscle stress.

4.3

Cause temporary blinding which will vary in duration depending upon the

intensity and character of the light source. Strobing of the light

depending on its intensity and speed can cause prolonged disability to a

person. The utilization of strobing light must include a legal review

to determine what liabilities may be incurred.

5. Light Intensity for Psychological Deterrence - Design Issues

Remember

that psychological deterrence is an intruder's belief and/or perception

(perhaps accurate, perhaps not) that security at a specific location

has diminished his or her ability to overcome the security measures in

place. Lighting, as previously mentioned, can be an important tool in

creating a psychological deterrence. The objective for designers of such

a lighting system is to provide illumination intensity sufficient to

convince an intruder there is a high probability of detection,

identification or apprehension.

6. Types of Lamps

In

casual conversation, lighting terms are often used imprecisely. These

are two terms which are often used interchangeably; however, in

discussing technical lighting issues, their correct usage is important

to avoid confusion.

These are:

Lamp - the actual bulb or tube which emits light when electrical energy is applied.

Luminaries

- the lamp, housing and all other hardware used in mounting and

focusing illumination; also referred to as lighting unit, fixture, or

instrument.

There are many different types of lamps used in modern protective lighting systems:

6.1 Incandescent

6.2 Fluorescent

6.3 Mercury vapor

6.4 Metal halide

6.5 High pressure (H/P) sodium

6.6 Low pressure (L/P) sodium)

Each

has its own unique characteristics which determine when the particular

lighting is suited to a particular task. For example, low pressure

sodium provides relatively high levels of illumination at low cost.

Often they are used to light highways; however, L/P Sodium lamps tend to

distort colors significantly. Using L/P sodium lighting for a parking

lot at a car dealership, therefore, would be inadvisable, since

customers would be unable to get a true representation of the color of

the vehicle before them.

Mercury

vapor, metal halide, and high-pressure sodium are known as

high-intensity discharge (HID) lamps. These lamps provide the highest

efficiency and longest service life of any lighting type. They are

commonly used to outdoor lighting and in large indoor areas.

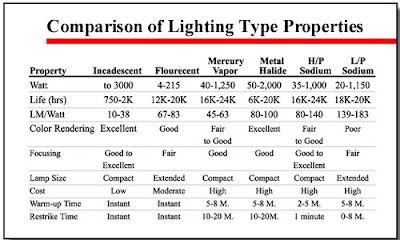

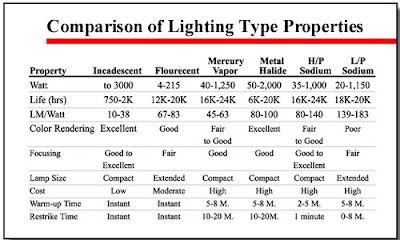

7. Illumination Quality

Factors to consider in selecting a lighting type are:

7.1 The lumens per watt

7.2 Color rendering

7.3 Focusing capability

7.4 Warm-up time

7.5 Re-strike time

7.6 Flicker rate

Illumination

quality is the combination of all these individual factors. As in all

security applications, determining the specific use for a system — in

this case lighting — will define the resources required — in this case

the illumination quality of the lighting system. Figure above provides

an overview of many of the factors effecting illumination quality. A

discussion of several of these factors follows.

7.1 The lumen per watt

Lumen

is a measure of illumination. Lumen per watt is a measure of

efficiency. It is the ratio of illumination to electrical energy used by

the lamp to create the illumination. Lumen (LM) per watt has

significant impact on the cost-effectiveness of the system.

7.2 Color rendering

Color

rendering is an important consideration if actual scene element colors

must be observed or color CCTV cameras are to be used to record the

scene. In such situations, it is important that natural colors not be

distorted.

7.3 Focusing capability

Focusing

is a luminaire's "spread;" that is, does it cover a wide area with

diffuse light, or can it be aimed in a narrow beam of intense light on a

small area. The intended use for a given lighting unit (object

illumination: physical deterrence, etc.) defines the type of lighting

unit required: wide or narrow focus.

7.4 Warm-up time

Warm-up

time is extremely important if maximum luminance is instantly required

at the time of activation. Compare the values in the table shown

previously.

Note

that some types of lighting require as much as eight minutes achieving

their optimum output level. In some security operations, that would

present an unacceptable risk.

7.5 Re-strike time

Re-strike

time is the period of time between a lamp's shut-down and its restart.

Some lamps can be restarted immediately; others must "rest" for as much

as 20 minutes before "re-striking." Along with warm-up time, re-strike

time is critical to systems used to protect persons or high property

value items, since such security systems cannot afford to be without

sufficient illumination for extended periods of time. Thus, the amount

of time needed to restore the system determines its value to the overall

security program. If instant re-strike is required, system designers

must include a capability for an automatic restart stand-by system.

7.6 Flicker rate

Some

lamps have as part of their characteristics varying degrees of flicker.

This may be most visible in the video produced by a CCTV camera using

certain lamps as a source of illumination. It appears as "jumps" or

rapid pulsing in the video. Flicker is a result of the alternating

current which supplies electrical power to the lamp. Some types of lamps

are more susceptible to flicker than others. In addition to affecting

video image quality, flicker rate has a more subtle effect. Individuals

exposed to flicker for long periods of time — while perhaps consciously

unaware of the phenomenon — can develop stress, and elevated levels of

stress has a negative impact on personnel both at the psycho-social

level and in terms of productivity.

Writer :

Writer :

|

Md. Ashiful Alam |

0 Comments